What is there to say about Hamilton that hasn’t now been said a million times before in the five years since the musical phenomenon burst onto Broadway? In those five years, Hamilton, the story of one of America’s most influential Founding Fathers, has sparked a mini revolution of passionate conversation about American history; inspired a dedicated fandom; and now, on the anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence, made the long-awaited jump from stage to screen. There was never any doubt that this moment would be huge: Disney paid a hefty sum of $75M for the rights to the musical, and it’s already right up there with The Mandalorian as one of the most high-profile original productions that Disney+ has to offer. But the outpouring of support for the film is still incredible to see: yesterday, the day of its release, Hamilton and a slew of other hashtags related to the musical were among the top trends of Twitter, and people (like myself) flooded social media with our reactions. Amid all the talk, what is there left to say?

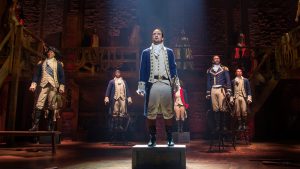

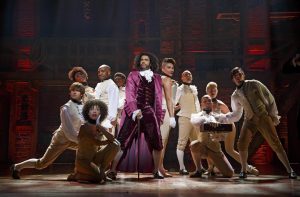

Well, the fresh new format in which the musical is being presented is cause enough for conversation; though, unsurprisingly, it’s not quite as interesting a subject for many as, say, the story or world-famous soundtrack. The movie was filmed over the course of three days, with cameras placed in the audience during two live performances of the show, before moving onstage to achieve a more cinematic experience – no easy feat, I’m sure, considering how many dancers are often crowding the stage, sometimes so many that we lose sight of our main characters (one of only a few flaws in the actual staging of the musical). Overhead shots are utilized in a number of scenes, particularly for duels. And extreme close-ups bring us nearer to the actors’ facial acting than was ever possible before, even for front-row audiences: from Daveed Diggs’ repertoire of eye rolls and dramatic sneers as a quirky, flamboyantly dressed take on Thomas Jefferson; to the spit flying from King George III‘s (Jonathan Groff) mouth as he sings his breakup song to America, assuring them they’ll come back to him once they’ve had their fun.

Diggs and Groff are among a number of standouts in the supporting cast who surround Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda) on his journey from poor immigrant to cornerstone of early American government. Diggs, notably, is one of several actors with two or more roles in the musical: before he transforms wholeheartedly into the fast-rapping character of Jefferson for the rousing second act, he is no less hilariously charismatic as the Marquis de Lafayette, America’s ally from across the Atlantic. Anthony Ramos is both Hamilton’s close friend John Laurens during the Revolutionary War, and then later his son Phillip (though the latter role is probably the more interesting of the two, I personally found Ramos to be more fun in the first, and I can’t wait to see him star in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In The Heights next year: if coronavirus hadn’t moved the film from its original June 26th release date, these past few weeks would have been a showcase of Lin-Manuel’s musical talent; but then again, if coronavirus hadn’t struck, we would still have been waiting until October of next year to see the Hamilton film on the big screen).

In the next tier (not in terms of talent, but based on how close they are to Hamilton) we have Christopher Jackson as the indestructible, untouchable George Washington, whose role as a mentor and something of a father figure to Alexander Hamilton is pivotal to the entire story. There’s Angelica Schuyler (Renée Elise Goldsberry), one of Hamilton’s many lovers and the most dynamic, at least initially, of the three Schuyler sisters. And of course we have Leslie Odom Jr., who brings plenty of fiery passion to the somewhat underwritten character of Aaron Burr, an ambitious political candidate forever walking unwillingly in the shadows of larger-than-life figures; the man whom history will forever paint simply as the villain in Alexander Hamilton’s story. And isn’t that the whole theme of the musical? It’s a story about the power of legacy, and how powerless we are to define what that is; as George Washington notes, you have no control over “who lives, who dies, who tells your story”.

The woman who tells Alexander’s story and who, in my humble opinion as a first-time viewer, seems like the understated heroine of the piece, is Eliza Hamilton (Phillipa Soo), Alexander’s wife and later his biographer. Her personal journey, running parallel to Alexander’s lofty dreams, may seem small and inconsequential to some: but in the end, she is the woman still alive fifty years after her husband’s death, still sifting through his writings and trying to piece together a more complete picture of the man, continuing the work on the garden he never saw bear fruit, on the symphony he left unfinished. Hamilton is really a story about people like Eliza, the people who will tell our stories when we’re gone, if we’re lucky enough; whose own stories often get overlooked amid all the heated discourse about their subjects. And Lin-Manuel Miranda isn’t really a modern day Alexander Hamilton, but he is a modern day Eliza, taking back control of a narrative that rarely if ever finds a place for the marginalized, but using this opportunity to uniquely inspect the story of America’s foundation through their eyes: the eyes of immigrants, the Black community and people of color, women, radical thinkers. Through embellishing the story with song and liberally picking and choosing which parts of Hamilton’s life story to adapt, Miranda is exercising his own right as a creative and a chronicler to reinvent Hamilton once again for a more modern audience. It’s hard to tell how Eliza herself would react to all the fame and glory she and her husband now enjoy – but one would hope that, like her musical counterpart, she would gasp in joy and awe at the audience gathered to witness her husband’s legacy in motion.

And then there’s Alexander himself: it’s hard to find many faults in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s performance, though it’s easy (and, in fact, important) to see the flaws in the complex character – apart from the historical fact that the real Hamilton was willing to stay silent on the issue of slavery whenever it suited him, the musical’s more liberal version of Alexander hurries through life, too concerned with his future to savor the present, too obsessed over protecting his legacy to be worried about what cost his actions have on those he loves. Alexander himself recognizes this and even sings about it on several occasions (most notably in “The World Was Wide Enough”), but once again it is Eliza who illustrates this point most brilliantly, in “Burn”, a heart-rending number sung in response to the devastating Reynolds Pamphlet scandal.

While we’re on the subject, my favorite subject, I want to highlight several of the songs which made the biggest impressions on me, at least during this viewing – first of many, I hope. Much to my surprise, neither “The Room Where It Happens” nor “Alexander Hamilton”, despite being the two most instantly recognizable songs from the show, would probably crack my top ten if I had to rank them all. “Burn”, my favorite off the entire soundtrack, draws our attention to the gaps in the narrative with its cleverly-constructed lyrics; George III has three catchy songs, each following the same melody, starting off with the sassy, self-righteous “You’ll Be Back”; Hamilton and Jefferson’s rap battles, particularly the first one, are exceptionally witty; and “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story”, the final song in the musical, gives the story an appropriately epic send-off, reminding us once again that the legacies we leave behind are never truly ours and ours alone, but belong just as much to the people who survive us, who keep those legacies alive long after we’re gone.

In conclusion, I doubt I’ve managed to say anything truly new about Hamilton, but what I hope is that by lending my voice to the conversation I can help to draw further attention to this rare achievement in American theater. This show may look like a scrappy, low-budget historical reenactment, but what it lacks in spectacle it more than makes up for in passion and unquestionable cultural impact.

Movie Rating: 9/10