POTENTIAL SPOILERS FOR THE RINGS OF POWER AHEAD!

So we’ve all seen the first teaser trailer for Amazon’s The Rings Of Power, right? I mean, it was the fourth most-viewed trailer in its first twenty-four hours of release after the first trailer for Spider-Man: No Way Home and the first and last trailers for Avengers: Endgame, so I’m just gonna assume we’ve all seen it by this point. I’m also gonna assume that a fair number of the record-breaking 257 million views on that Rings Of Power teaser came from people who aren’t necessarily familiar with the characters, events, and locations being portrayed in this prequel to The Lord Of The Rings.

And that’s totally okay, by the way. I won’t be asking for your signatures in Tengwar script to prove that you’re a “true fan”, because frankly, even if I did, I (*pause for dramatic effect*) don’t know how to read or write Tengwar myself! Heck, I might as well tell you now, I only know, like, ten or fifteen Elvish words in total and virtually none of the grammar that’s supposed to go in between.

Okay, so maybe not the wisest thing to admit while simultaneously trying to position myself as a reliable source of information on the deep lore of J.R.R Tolkien’s legendarium, but (a) my point is that this can be an intimidating fandom but it really doesn’t matter to me whether you’ve read The Lord Of The Rings and its appendices twenty times, or whether you’ve never read a word of Tolkien in your entire life but were intrigued by something in the teaser trailer for The Rings Of Power, because I try to make my content accessible to everyone, and also (b) I actually have read the books and appendices more than twenty times, so please trust me! I absorbed the lore better than I did the languages, I swear.

To prove it, today we’re going to be diving into the nebulous and often contradictory lore surrounding one of the most enigmatic characters in all of Tolkien’s works, and the rumored protagonist of The Rings Of Power – the Lady Galadriel. The marketing for Amazon’s series makes it clear that Morfydd Clark’s Galadriel is, if nothing else, the most competitive of several candidates vying for top-billing in a large ensemble cast rounded out by Robert Aramayo’s Elrond, Maxim Baldry’s Isildur, and Markella Kavenagh’s Elanor “Nori” Brandyfoot (each of these characters warrants their own introductory post in good time, but I wanted to start with Galadriel because she just so happens to be my favorite character in Tolkien’s legendarium).

And despite how difficult it is to piece together a clear account of her life from J.R.R. Tolkien’s writings on the subject, Galadriel is the obvious choice to lead. Because if The Rings Of Power, a prequel distanced from the events of The Lord Of The Rings by a span of over three-thousand years, is going to be commercially successful, it needs to provide fans of The Lord Of The Rings (the books and the films) with something they can grab hold of that makes them feel safe and comfortable in this unfamiliar era of Middle-earth’s history.

And amidst all the characters of that era whose names and great deeds had faded into legend by the time of The Lord Of The Rings, characters like Isildur and Elendil and Gil-galad, there is one who stands out from the rest – one whose life-story spans the entirety of Middle-earth’s recorded history, from the literal beginning of time to the very last date etched in the Tale of Years. And that is Galadriel.

Galadriel is approximately 8372 years old by the time of The Lord Of The Rings – technically making her the second-oldest Elf in Middle-earth (at least that we know of) after Círdan the Shipwright, who is somewhere between 10741 to 11364 years old. Characters like Treebeard and Tom Bombadil are significantly older than both of them, though by an indeterminate margin (Treebeard is estimated to be around 30000 years old by fans, while Tom claims to predate the first rivers and trees in Middle-earth, making him roughly 50000 to 60000 years old). But the advantage Galadriel has over all these other characters is that she actually…did stuff.

By that, I mean she’s integral to the story that The Rings Of Power plans to tell over the course of five or more seasons; the story of the Second Age of Middle-earth, beginning with the forging of the Rings of Power and concluding in the tumultuous War of the Last Alliance. I am aware that Círdan also participated in these events, to a slightly lesser extent than Galadriel, but he lacks the name recognition necessary for a protagonist in this case, as well as a clearly defined character arc. Galadriel possesses both.

And yet…there is one itty-bitty problem with Galadriel being the protagonist. You see, even after publishing The Lord Of The Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien couldn’t help but continue altering fundamental aspects of his characters’ backstories, and Galadriel was the victim of some pretty aggressive edits the author made near the end of his life, meaning there is no “canonical” version of her story for Amazon to adapt. Even the stray bits and pieces of Galadriel’s backstory provided in the pages of The Lord Of The Rings subtly contradict details in the book’s own appendices.

Before we go any further, I ought to note that Amazon has the rights to The Lord Of The Rings and its appendices (and The Hobbit), but Rings Of Power showrunners Patrick McKay and J.D. Payne have vehemently denied that their deal with the Tolkien Estate granted them access to the author’s posthumously published writings, including The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, which altogether contain the most complete version of Galadriel’s story. We do not know the truth of the matter just yet.

The Silmarillion is a history textbook covering the First Age and Second Age of Middle-earth in great detail and then kinda glossing over the events of the Third Age (the period of time in which The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings take place). J.R.R. Tolkien began writing it in the early 1910’s, and at one point intended to publish it alongside The Lord Of The Rings so that readers would understand the frequent references to in-universe historical events, legendary battles, and tales of ancient heroes. He never finished, leaving his youngest son Christopher with the daunting task of having to compile his notes into a workable narrative.

The published Silmarillion is still regarded as inherently less “canon” than The Lord Of The Rings because it wasn’t ever approved for publication by J.R.R. Tolkien himself and had to be heavily abridged, but the tale it tells of Galadriel is one that many fans – including myself – have fallen in love with and regard as canon because it’s the version of Galadriel’s story alluded to in The Lord Of The Rings, and the only one that makes any sense.

As for Unfinished Tales, the nature of the work (an anthology of stories Tolkien started, but never had the time or inclination to complete) means that it is inherently less cohesive than The Silmarillion, but it also contains a level of detail that The Silmarillion does not possess, and that makes it a rewarding read for anyone interested in the rich lore of Middle-earth. Some of the most well-known anecdotes about Galadriel’s life come from Unfinished Tales, and are fairly easy to superimpose onto the version of her story in The Silmarillion. Nonetheless, I will point out these instances as we proceed.

Per The Silmarillion, Galadriel was born in the Undying Lands of Valinor at a time when the High Elves were still under the protection of Middle-earth’s gods. For the sake of simplification, we’re just going to pretend that time existed as a concept back when Galadriel was born, even though it…didn’t. Middle-earth didn’t have a sun or a moon back then, so there were no days or months or years, but there were these durations of time called Valian Years, which correspond to either nine or 144 of our solar years depending on which of Tolkien’s writings on the subject you regard as more “canon”, and as if that isn’t confusing enough you also have to factor in that the passage of time literally feels slower in Valinor, so 144 solar years might feel like just one solar year to a Valinorean, and…argh, I said we were just gonna pretend that time existed, and I’ve already failed!

Anyway…when Galadriel was born, there was no sun and moon, so the only natural light emanated from the stars (which were created by the goddess Varda), and from two trees planted by the gods in the middle of Valinor, which glowed brightly and bathed the Undying Lands in a warm, purifying light. All of the Elves touched by this light retained a kind of magical residue on their bodies that formed an aura, but Galadriel is the only Elf we know of whose hair, specifically, was believed to have caught this residue and became “lit with gold” as a result. Keep that in mind; it’ll come up again later.

The Silmarillion doesn’t have a whole lot to say regarding Galadriel’s early life in Valinor. Unfinished Tales, however, tells us that when she was still young, “she grew to be tall beyond the measure even of the women of the Noldor; she was strong of body, mind, and will, a match for both the loremasters and the athletes of the Eldar in the days of their youth”. The famous letter in which Tolkien described Galadriel as having once been “of Amazon disposition” is not included in either book, but I’m mentioning it here because The Rings Of Power appears to be extrapolating on that idea.

As she was the granddaughter of the High King Finwë by way of his second marriage, we can safely assume she lived in the capital city of Tirion-upon-Túna – a location that had never appeared in live-action until last year, when the first official image from The Rings Of Power revealed a Valinorean panorama including Tirion, the Two Trees, and an unidentified figure rumored to be Finrod, Galadriel’s eldest brother. They were beloved by their grandfather Finwë, but treated with contempt by Fëanor, Finwë’s eldest son and the only one born to his first wife, Míriel.

Fëanor didn’t approve of his father’s second marriage, and The Silmarillion assures us that, like, a whole bunch of High Elves felt the same way. Names? You’re asking for names? Uh…well, the narrator talked to at least seven people who were definitely not the sons of Fëanor wearing fedoras and fake mustaches. All joking aside, it’s a weird part of the book where it feels like the devoutly Catholic Tolkien really wants to draw some correlation between Finwë’s remarriage and Fëanor being a jerk, but he doesn’t quite manage it and then backtracks to add that it’s a good thing Finwë did have more children, because someone needed to keep Fëanor in check, and it sure as hell wasn’t gonna be any of his kids.

Needless to say, everyone in Valinor was pretty relieved when Fëanor decided to channel his pent-up frustration with his father into seemingly inoffensive pastimes like art and alchemy, but Finwë’s other children and grandchildren were especially happy because it meant that for the greater part of any given Valian Year Fëanor and his sons would be holed up in their forge, and nobody had to interact with them except at dinner parties, and on those occasions you just had to hope that Fëanor would be too busy showing off his new inventions for him to find time to pick on you. Sometimes he’d even invent something useful, like an alphabet, and then other times it would just be weird, like when he designed a bunch of creepy all-seeing orbs that could stare at you from across a continent.

Most people would choose to rest on their laurels after creating the alphabet, but Fëanor wanted to one-up himself and the gods at the same time, because what could possibly go wrong with a plan that involves potentially incurring the wrath of a pantheon of omnipotent deities on whom you and your people rely for literally everything, including protection from a Dark Lord who wants to turn you all into orcs for his nihilistic amusement?

Fast-forward a few Valian Years, and Fëanor emerges triumphant from his forge with three jewels called Silmarils (hence The Silmarillion). These jewels, these Silmarils, were imbued with some of the precious light of the Two Trees, making them eerily similar to NFTs in that they served no real purpose except to give the possessor (i.e. Fëanor) a false sense of ownership over something he did not create and which was already freely accessible to everyone in Valinor; the only difference being that the Silmarils actually turned out to be worth something in the end. In Unfinished Tales, it’s even suggested that the idea for the Silmarils came to Fëanor after studying Galadriel’s hair, and that he begged her three times for a sample to use in his experiments, but “[she] would not give him even one hair”.

The gods decided to let Fëanor keep his NFTs as long as he shut up about the limitless potential of cryptocurrency, but the Dark Lord Morgoth was obsessed with the idea of taking them for himself (which should tell you something about the type of people who want to own NFTs), and he quickly realized that while Fëanor’s covetous attitude toward the Silmarils meant they were kept closely-guarded at all times, it also meant the Elf would walk blindly into any trap if he felt his Silmarils were threatened. Morgoth laid the groundwork for his trap by traveling among the Elves and regaling them with tales about the lands in Middle-earth they could rule if only the gods would allow them to leave Valinor.

It’s safe to assume that Galadriel was one of the Elves on whom Morgoth’s words made a strong impression. Because when the Dark Lord finally stole the Silmarils and fled to Middle-earth, leaving a trail of dead bodies (including poor old Finwë’s) for Fëanor to follow, Galadriel unexpectedly joined Fëanor in calling for a man-hunt to find the Dark Lord and bring him to justice. She didn’t particularly care about reclaiming the Silmarils, but “she yearned to see the wide unguarded lands and to rule there a realm at her own will”, in stark contrast to her father Finarfin and brother Orodreth, who “spoke softly” in an effort to cool Fëanor’s hot temper, and to her brother Finrod, who hated Fëanor’s guts and made no secret of it.

Something that nobody seems to have considered while arguing over whether or not to leave Valinor was whether or not they could leave Valinor. No one had ever tried before. The Undying Lands were separated from Middle-earth by a wide ocean at the time, and the only land-bridge connecting the two continents lay somewhere in the uttermost north. So for a while, everybody just kinda walked aimlessly along the beach while they waited for somebody at the front of the line to settle on a direction. The House of Finarfin, including Finrod, is said to have been at the rear – “and often they looked behind them to see [Tirion]“.

It would seem out-of-character for Galadriel to be one of those glancing over her shoulder at the home she was about to leave behind, considering how eager she was to leave, but it would probably make even less sense for her to be amongst Fëanor’s folk at the front of the line; the reason being that Fëanor actually had a destination in mind – Alqualondë, the coastal port-city of the Sea-elves, Galadriel’s family on her mother’s side. He had assumed the Sea-elves would just give him all of their ships for free (reasonable dude, Fëanor), and was stunned speechless when they essentially told him to bugger off. So he killed them and took their ships by force.

The Elves who arrived late to the battle didn’t know what the hell was going on, and just started stabbing people randomly, turning the harbor of Alqualondë into a bloodbath. The Silmarillion simply never tells us whether Galadriel, Finrod, and Finarfin took part in this “Kinslaying”, and avoids implicating any of them in the atrocity at all – an imperfect solution on Christopher Tolkien’s part to a problem that J.R.R. Tolkien appears to have encountered every time he rewrote Galadriel’s story and reached this pivotal moment; how to get Galadriel to Middle-earth with only a medium-sized blemish on her reputation for goodness?

A manuscript published in the Unfinished Tales tells us that Galadriel indeed took part in the Kinslaying, but “fought fiercely against Fëanor in defence of her mother’s kin”, and this is the idea that Tolkien seems to have been the most stubbornly satisfied with…for a little while, at least. In recent months, this passage has been quoted and discussed at length, as it provides textual evidence for The Rings Of Power‘s interpretation of Galadriel as a warrior, and paints a pretty epic picture of her.

It’s unfortunate, then, that this passage doesn’t fit comfortably within the broader narrative and never has, because Tolkien still needed Galadriel to continue following Fëanor after the Kinslaying – and whether or not it makes sense for her to do so after Fëanor killed many of her people, it’s completely unlike Fëanor to allow her to do so after she had presumably killed or injured some of his. Even though he eventually chose to leave Galadriel and most of the House of Finarfin stranded in the far north (taking with him to Middle-earth only those “whom he deemed true to him”), to argue that that was his plan all along and that he was playing the long game requires a leap in logic I’m not willing to make.

Unfinished Tales contains a rapid, fascinating summary of another version of Galadriel’s story that Tolkien had sketched out shortly before his death in 1973. In this rewrite, he did what most writers do at least once when confronted with a case of characters not doing what they’re supposed to do, and started over from scratch. Galadriel abruptly ceased to be a member of Fëanor’s rebellion and became thoroughly independent from him, with her own goal of sailing to Middle-earth as an adventurer. She just happened to choose a really bad day to set out from Alqualondë, and had to fight Fëanor and his people as they tried to board her ship. This version still gives us a warrior Galadriel (and a seafaring warrior Galadriel at that), but it does remove a layer of complexity from the character that I would have missed.

To recap, the published Silmarillion doesn’t mention Galadriel in connection with the Kinslaying at Alqualondë. By the time we catch up with her again, four whole pages have passed since the Kinslaying and a lot has happened. The gods finally got involved by sending a message to Fëanor (“accidentally” blind-CCing all the Elves in the process) to tell him that he could go to Middle-earth and get swallowed by a dragon for all they care, but that anyone who followed him would be banished from Valinor forever, and when Morgoth inevitably killed them all, even their souls would be forbidden from entering the halls of the dead.

Finarfin didn’t need to be told twice to get the hint, and chose to return to Tirion and become High King of the twenty or so Elves left in Valinor. Fëanor and the rest of the Elves continued northward, following the coast of Valinor on land in their ships – until at some point, Fëanor decided that it would be easier to just steal the ships and set sail for Middle-earth, leaving the other Elves stranded in the frigid wastelands north of Valinor. Galadriel finally reappears, and along with her brother Finrod heroically takes command of the dire situation and leads the Elves across the icy land-bridge connecting Valinor to Middle-earth.

This is probably as good a time as any to point out that Galadriel and a group of Elves can be seen traversing an icy landscape in the first teaser trailer for The Rings Of Power, although this scene is said to take place in Middle-earth and not in Valinor, as some had hoped. The giveaway is the bright sunlight beaming down on Galadriel in those shots in the trailer – at the time that Galadriel led the Elves across the Grinding Ice in pursuit of Fëanor, the sun and moon had still not been created.

Unfortunately, Tolkien wrote very little about the crossing in The Silmarillion, and even less in Unfinished Tales. Many Elves died, whether by starving to death or drowning under the ice, but enough survived and were hardened by the experience that their army still made for a fearsome and awe-inspiring sight when they came down from the north into the lands of Middle-earth at the very moment that the sun arose. Morgoth cowered in his fortress under the earth, and his orcs fled before the Elves and permitted them to march straight up to Morgoth’s front gate and beat upon the doors, and Galadriel was probably there but Tolkien doesn’t tell us exactly what she was doing.

With the dawn of the sun, the First Age of Middle-earth officially began. Oh, you thought we were in the First Age already? Haha, no, all of that was just the Years of the Trees. The First Age, however, only lasted about six-hundred years (the Second and Third Ages, for comparison, span over three-thousand years each), and for most of this time Galadriel stayed in the forest realm of Doriath. She and Finrod were invited there by King Elu Thingol (who was the brother of their maternal grandfather), and Galadriel fell in love with an Elven prince named Celeborn whom she met there.

If you thought Galadriel’s backstory was complex, don’t even get me started on Celeborn. In The Lord Of The Rings and the published Silmarillion, it’s mentioned that he’s a “kinsman of Thingol”, which sounds about right…until you remember that Galadriel is also a kinswoman of Thingol, and before you know it you’re poring over fictional family trees desperately trying to prove that Galadriel and Celeborn are not first cousins, they can’t possibly be first cousins…right? Well, yes and no. It depends on which version of Galadriel’s story you’re reading. They’re only first cousins in the version where she sets sail from Alqualondë on her own ship. Before that, they were just second cousins.

While Finrod went off and established his own kingdom in Nargothrond, Galadriel remained in Doriath with Celeborn, learning magical arts and lore from Elu Thingol’s wife, Melian, a minor goddess. As far as we know, she took no active part in the wars against Morgoth or in the later efforts by Fëanor’s sons and other heroes to reclaim the Silmarils, nor did she immediately seek power for herself – probably because she understood just by looking around that until Morgoth was defeated and Fëanor’s family were dead, the Elves would have little peace in Middle-earth. Also, Finrod had once prophesied that Nargothrond would fall, which can’t have filled Galadriel with much confidence for her own prospects.

Finrod’s prophecy came to pass (prophecies have a way of doing that), but neither he nor Galadriel was there to witness the Sack of Nargothrond and the slaughter of Finarfin’s folk. Finrod died in the year 465 of the First Age, and sometime between then and 495, Galadriel packed her things and left Doriath, crossing the Blue Mountains into the unoccupied lands of Eriador. She is sometimes said to have done so alone, but Celeborn probably joined her no later than 506, when he is said to have fled the Sack of Doriath.

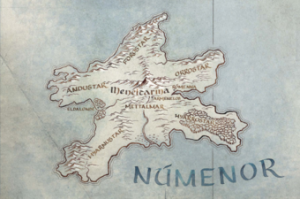

Less than a hundred years later, the War of Wrath happened (in which Morgoth was finally vanquished by the gods, and the last of Fëanor’s seven sons either died or disappeared), and at this point The Silmarillion completely loses track of Galadriel in all the chaos and Unfinished Tales picks up their plot-thread in a short text which Christopher Tolkien described as “almost the sole narrative source for the events in the West of Middle-earth up to the defeat and expulsion of Sauron from Eriador in the year 1701 of the Second Age”. These are the events that The Rings Of Power hopes to adapt across its first season.

In this story, Galadriel and Celeborn cross the Blue Mountains into Eriador after the War of Wrath and settle at various locations between Lake Nenuial in the north-west and Eregion in the east, under the shadow of the Misty Mountains and close to the Dwarven city of Khazad-dûm. At some point during their travels, Galadriel gave birth to a daughter, Celebrían (and for the first and only time is mentioned as having a son, Amroth, but this detail is never reflected in The Lord Of The Rings, so I don’t regard it as canon).

Celeborn had no affection for Dwarves, but Galadriel is said to have “looked upon the Dwarves also with the eye of a commander, seeing in them the finest warriors to pit against the Orcs”. When she was ousted from Eregion in a coup led by the craftsman Celebrimbor and a mysterious stranger named Annatar, the Dwarves allowed her safe passage through Khazad-dûm to the woodland realm of Lórinand on the eastern side of the Misty Mountains.

Celeborn “remained behind in Eregion, disregarded by Celebrimbor”.

It soon became apparent to all that the stranger named Annatar was none other than Sauron, formerly the lieutenant of Morgoth, and that he had planned to manipulate the Elven craftspeople of Eregion into forging Rings of Power with which to ensnare the free peoples of Middle-earth. Celebrimbor therefore crossed the Misty Mountains and took counsel from Galadriel, who advised him to give her one of the Rings (no ulterior motive there, that’s for sure!) and to hide the others far from Eregion.

Of the nineteen Rings of Power forged by Celebrimbor and Sauron, sixteen came into Sauron’s possession when he attacked Eregion – but three eluded him forever, and these were the three given to the Elves; one to Galadriel in Lórinand, and two to Galadriel’s young cousin Gil-galad in the realm of Lindon. Sauron considered attacking Lórinand, but the doors of Khazad-dûm were shut and he could not cross the Misty Mountains. Instead, he went after Gil-galad, because there were only so many Elves to whom Celebrimbor would have entrusted a Ring of Power and their identities weren’t exactly secret.

Sauron came very close to defeating Gil-galad and capturing his Rings, but was foiled at the last moment by a Númenórean fleet out of the west, who drove him out of Eriador and back to the shadowed realm of Mordor. “For many years the Westlands had peace”, and in this time Galadriel and Celebrían returned over the Misty Mountains and reunited with Celeborn in the haven of Imladris. Gil-galad joined them for a war-council in which it was decided that he should give one of his Rings of Power to the young lord Elrond of Imladris – who by an extraordinary coincidence had just fallen in love with Galadriel’s daughter, Celebrían (nothing suspicious about that, that’s for sure!)

For more context on Elrond and the Númenóreans, I suggest you check out some of my earlier posts, namely this one and this one – although I will be continuing this series soon with a post about the Númenórean prince Isildur. It should be a lot easier to write than this one, which required me to have several books and literally dozens of search-tabs open simultaneously.

As for Galadriel, well, that’s her entire story through The Rings Of Power season one, at least based on what we currently know. I can’t promise that everything you’ve read in this post will make it into the show, but I do believe that having this context will help a lot of people – particularly new fans – better understand the characters who inhabit Middle-earth, and I hope you’ve enjoyed it. Be sure to share your own thoughts, theories, and opinions, in the comments below!